Table of contents:

The original postscript version of the newsletter is available here.Help your friends: We depend upon each other to get into the air. Each launch involves at least three club members in addition to the pilot (the tow pilot and one person at each end of the tow rope), and each launch of a student pilot requires at least one more (the instructor). We hope that club members will try to help launch three or four gliders for each launch they take themselves. Furthermore, it takes time to get the club gliders ready for flight in the morning and tie them down in the evening. We expect everyone flying club ships to arrive early enough in the morning to help get the gliders ready to fly, or to stay late enough in the evening to help put them away, and we encourage students to plan to spend the entire day at the field. Finally, we all depend on the day's DO to organize the activity on the field, and this less-than-glamorous job is less of a burden when a large number of people share the job. We expect all soloed students and all rated pilots to serve as DOs unless they are instructors, tow pilots, or have been specifically excused from this duty. If you have any questions or comments about these expectations, please feel free to contact Al Gold, our director of operations, at (617) 926-9076 or gold@deas.harvard.edu.

New members: We have gained four new members.

Jack Campbell joined the club in early June. "Although my name is John, most people call me Jack. I am 55 and have recently retired from AT&T after 25 years. There I worked mostly in Boston but did stints at Bell Labs in New Jersey and in France, Belgium, and Switzerland. Since retiring, I have done some consulting in Brazil with Telebraz regarding their privatization and some small projects here in New England. I live in Boylston, which is near the Sterling airport, and I'm getting married on June 20, so I won't be around for a few weeks. Other hobbies: I bought a Harley as a retirement gift to myself, golf, sailing, and my real passion is travel. I was out on the Harley one day and stopped at the airport on a Wednesday afternoon to watch, and someone said I should give it a try. I gave it some thought and returned on Saturday to do just that."

Tom O'Brien joined over the July 11 weekend. "I joined the club a couple of weeks ago and am looking forward to learning more about soaring. I hold a private certificate for airplanes, and hope to continue with both types of flying. I had seen Sterling airport from the air and also had driven by to check out the airport on a few occasions. That was when I had first seen the gliders and it peaked my interest. After watching the soaring and talking with a number of very helpful people, I decided to go for a demo flight and enjoyed it as much as I thought I would, so I joined the club. I'm looking forward to lots of soaring hours."

Chris Craig joined on June 28, and Lee Winder joined over the July 11 weekend. Chris is a full-time student (thirteen years old) and Lee is a graduate student in aero/astro at MIT. Both are new to flying.

Departures: Errol Drew announces, "For those wondering what I'm still doing here in the US after rumors of imminent departure (spread freely by none other than myself) have been so long circulated, I reluctantly confirm that it's all true. We shall be moving back to England, that land of low cloud bases and abundant air restrictions, very soon. Some time in July, Joanne and I will be over there for around three weeks, after which I will return for probably a short while to pack our goods and ship it back. Meanwhile you can expect to see me around from time to time as my business interests, though now much reduced, still exist in Foxborough and I shall return every two months or so. This will give me a chance to keep contact with the many soaring friends made here while in the US who I shall always be glad to see. Joanne is looking forward to taking up a music teaching post at one of the British schools in September. Meanwhile the care of glider 204 is being entrusted to my fellow syndicate partners who I hope will enjoy flying her around the New England skies as much as I have while here in the USA."

Maintenance: Jim Emken reports, "117BB is back in service after its annual inspection. The next annual will be in October for the 1-26. 117BB has a new electric Cambridge audio vario, the same make and model as the one in the L-33. The 1-34 is having one installed this week, and 118BB will be having one installed the following week. All of the club gliders now have new batteries. The batteries are all the same, wired with the same connectors, and can by used in any of the club gliders. Leave the batteries in the gliders, but remember to turn off the electric varios at the end of the day. As long as the electric varios are not left on overnight, the batteries will be able to run the varios for months at a time. If you find that a vario has been left on overnight, see to it that the battery gets put on the charger, as it is bad to leave them run down. There will be a new charger on the desk in the MITSA office wired up with a connector matching the connector on the batteries. The charger can fully charge a battery overnight and it has an automatic "float" feature that allows a battery to remain on charge indefinitely. It is therefore okay to leave a battery on charge all week until the following weekend. All of the old batteries are gone, so there shouldn't be any confusion. All of the club gliders desperately need waxing. There is an ample supply of wax and rags in the cabinet in the MITSA office. We all need to pitch in and wash and wax the gliders. I will be recruiting members to pitch in at the end of each day after flying."

July 9, 1998

All members of the board plus John Wren and Adam Dershowitz were present.

MITSA associate membership: It was moved, seconded, and passed that the president's proposal for associate membership be enacted. Associate membership is a low-cost way for members of other Sterling-based clubs to fly with MITSA. Associate members have equal rights and responsibilities with existing MITSA membership categories except that they do not vote and their annual dues are correspondingly lower. An applicant for associate membership must either already be a member of a soaring club based at Sterling as of July 1, 1998, or have been a member in good standing of such a club for a minimum of one year. The annual dues for 1998 associate membership have been set at $100. In addition, MITSA charges a $100 sign-up fee. Because MITSA income is derived primarily from tow fees, a $10 hook up fee is charged for launching a MITSA glider with a non-MITSA tow plane, regardless of membership category.

Operations with GBSC at Sterling: The responsible duty officer should check in with the airport manager at the beginning of glider operations so that the airport manager is aware of the person in charge for the day. Any safety issues which arise because of different procedures by the two organizations should be passed to John Wren who will act as our contact point for resolving such issues. A barbecue with GBSC was planned for Saturday, July 11, at the end of flight operations.

New tow plane: Bill Brine reported by speaker phone that the new tow plane subcommittee has looked at a candidate 1956/57 Cessna 182 in Saratoga, New York, which has been used at least ten years as a tow plane. Despite its age, it appears to be in good mechanical condition with a new engine. Drawbacks are that it has no view to the rear other than a mirror, still has its original bladder fuel tanks, tows at 75-80 miles per hour, and will need new propeller, paint, tires, and so on. The board asked the subcommittee to have the plane inspected and evaluated by an A&P mechanic. The board finalized details of the tow plane bond issue. MITSA bonds are being offered for sale in $500 units (minimum of two) at either 4% annual interest, repayable after seven years, or 5% annual interest, repayable after ten years. Speak with Steve Glow to sign up or for more complete details.

Maintenance: The fleet is in urgent need of waxing. Two of the trailers need painting. Jim Emken will obtain supplies and recruit members to assist in the work after flying. Phil Gaisford will contact John Flynn about disposal of the large unwanted trailer.

Finances: Steve Glow gave an encouraging report on the club's financial condition. The club's single-seaters are being grossly underutilized.

Membership: Joe Kwasnik reported progress on the design of a logo for advertising posters, t-shirts, and SOAR MITSA bumper stickers.

Next meeting: The next meeting will be held in August at Carl Johnson's home.

| Date | DO | Instructor | AM Tow | PM Tow |

| 8/1 | Koepper | Bourgeois? | Proops | Clark |

| 8/2 | Kucan | Krueger | Dershowitz | Easom |

| 8/8 | Kwasnik | Johnson? | Friedman | Gamon |

| 8/9 | Loraditch | Rosenberg | Hollister | Kazan |

| 8/15 | Nordman | Bourgeois? | Proops | Clark |

| 8/16 | MacMillan | Wren | Dershowitz | Easom |

| 8/22 | Tsillas | Krueger | Friedman | Gammon |

| 8/23 | Timpson | Johnson? | Hollister | Kazan |

| 8/29 | Sovis | Baxa | Fletcher | Proops |

| 8/30 | Watson | Krueger | Poduje | Clark |

| 9/5 | Blieden | Bourgeois? | Dershowitz | Easom |

| 9/6 | Gaisford | Rosenberg | Fletcher | Gammon |

| 9/7 | Gold | Baxa | Hollister | Kazan |

| 9/12 | Nordman | Krueger | Friedman | Proops |

| 9/13 | Koepper | Wren | Poduje | Clark |

| 9/19 | Blieden | Bourgeois? | Dershowitz | Easom |

| 9/20 | Brine | Rosenberg | Fletcher | Friedman |

| 9/26 | Wong | Baxa | Gamon | Hollister |

| 9/27 | Loraditch | Krueger | Poduje | Kazan |

| 10/3 | Kwasnik | Bourgeois? | Proops | Clark |

| 10/4 | MacMillan | Wren | Dershowitz | Easom |

The following story is based on excerpts from articles, sent to me by Morrie Tuttle, that appeared in The Times (London) and The New York Times on June 1 and June 8. --Editor

Lorne Welch, crack British glider pilot and yachtsman, coauthor of the soaring classic New Soaring Pilot, and participant in two of the most storied escapes by Allied prisoners during World War II, died at his home in Farnham, England, on May 15. He was 81.

A prisoner of war with uncommon flair, Welch was being held at the Stalagluft III prison camp in Silesia when he rigged the tunnel ventilation system that was used in one of the largest mass breakouts by Allied prisoners during the war, an incident that became the subject of the 1963 movie "The Great Escape." Later, as a prisoner at Colditz, the 700-room Saxon castle the Nazis used to hold incorrigible escape artists, he helped design a two-man glider with a 32-foot wingspan that was to be launched from one of the castle's towers. It was never tested because the prisoners were liberated by American troops before an attempt could be made. After the war, Welch became the first man to glide twice across the English Channel--first from Redhill to Brussels in a Weihe, and then in a two-seater with a passenger--and to fly with the British team in four world gliding championships.

After secondary schooling at Stowe, Welch, who had an instinct for solving technical problems but no formal training as an engineer, worked with both marine and aircraft engines, designed and built a sailing dinghy, and flew gliders before joining the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. With the RAF, he did his elementary pilot training at Woodley, and with only 110 hours solo was sent on to an instructor's course, which he completed just before Christmas 1939. With a grand total of 124 hours as pilot in command, he was posted to RAF Elmdon to teach Royal Navy midshipmen to fly Tiger Moths.

In September 1941, he was posted to Cranwell to convert to twin-engined Oxfords, and in April 1942, assessed as an exceptional pilot, he moved on to Wellingtons. He might have remained safely on training duty if, a month later, the British had not announced plans to to launch 1,000 bomber raids on Nazi Germany, a strategy that required the services of virtually every military plane and pilot. Welch went on the first raid, the notorious onslaught on Cologne, as second pilot. He was captain for the next raid, to Essen, and again on the third raid, to Bremen. His fourth raid was to Dusseldorf--still in a training school Wellington.

This time he was shot down over Holland, landing his barely controllable aircraft in a field with an engine out and wheels hanging. Rather than flee, Welch chose to remain with his injured bombardier and allowed himself to be taken prisoner. After the wounded flier had been taken to a hospital, Welch made a bid for freedom, breaking away at the Amsterdam train station. But, when his pursuers fired into the crowd, he gave himself up in order to save the lives of the civilians.

Sent to Stalagluft III, he was given a room in which a model glider hung above a bunk--which began a long friendship with the prisoner who had carved it. They endlessly discussed escape, including the building of a glider to fly over the wire. At the same time, he was recruited into an real escape plot. Welch was assigned to build a ventilation system for "Harry," one of three 300-foot tunnels being dug 30 feet beneath the ground. He used parts of two beds, two duffel bags, nine coat hooks, four hockey sticks, four ping-pong paddles, and a bit of shoe leather to construct a bellows system connected to the tunnel by a series of powdered-milk cans. Of the 76 men who made their way through Harry the night of March 24, 1944, only three made it safely to freedom. Of the 73 who were recaptured, 50 were executed on orders from Hitler, an atrocity that was avenged after the war when the executioners were hanged for war crimes.

For all his contributions to the great escape, Welch was not among those who went through the tunnel. Months earlier, he and 23 other officers, pretending to be on delousing duty, had simply walked through the main gate, wearing fake German uniforms made in a secret prison tailor shop.

Their plan was to find an airfield, "borrow" a German airplane, and fly to Sweden. The pair spent a week living in the rough before they found Kupper airfield and a Junkers W34 parked outside the control tower with enough fuel for Sweden. As they climbed aboard it looked perfect, but the German crew came back too soon and ordered the two RAF officers to start it for them.

Next day the pair tried to steal another airplane, but were caught--fortunately by the Luftwaffe and not the Gestapo, who would have looked with less favor on their uniforms. The two were obvious candidates for Colditz. With its high, thick walls soaring above mountain bluffs and with more guards than prisoners, Colditz was considered escape-proof. But of 191 recorded escape attempts, 31 were successful. Indeed, for all the German precautions, it was a tribute to the prisoners' ingenuity that it was not until half a century later that workmen found a secret radio that had kept the prisoners abreast of war news.

By far the most audacious of the escape plots was the construction of a full-sized, two-man glider in a walled-off section of the castle attic. By the time Welch arrived at Colditz, Jack Best and others were building the famous glider, and they asked Welch as an aeronautical engineer to verify that the glider, made of bed slats covered with millet-treated sleeping-bag cloth, would withstand the stresses of flight, including being launched by a catapult powered by the five-floor drop of a concrete-filled bathtub. Although the glider's design was later judged airworthy by aviation experts, what might have been the most spectacular escape of the war was made unnecessary by the arrival of American forces in April 1945. When Colditz was liberated, the glider was ready and the prisoners had great satisfaction in rigging it in front of open-mouthed Germans, who had no idea that part of their attic had been walled off for a workshop.

Home at last after his liberation by the Americans, Welch returned to Farnborough to work on rocket motors before becoming chief instructor of the Surrey Gliding Club at Redhill, a test pilot for new aircraft for the British Gliding Association, a British team pilot in four world championships, and author of several books on gliding. He was also project engineer for the first British variable geometry glider, Sigma, as well as its test pilot. He later worked on fiberglass processes.

Lorne Welch married Ann, a pilot and sailor, in 1953. She and their daughter survive him.

This is a flight I have been meaning to report on for quite some time. Though we frequently encounter wave on our cross-country flights to the west of Sterling, this was the first such flight to be largely conducted using wave lift. July 19, 1997, was a typically not-too-busy day at Sterling. The wind was from the northwest, moderate in strength. The sky contained an encouraging scattering of cumulus, and it was soon determined that cloud base was over 5,000 feet, more than adequate for comfortable cross-country flight.

The first sign that this was going to be an unusual day's soaring occurred as I approached Gardner. About this time the cumulus reorganized themselves from the scattering mentioned earlier into regular cloud streets. Significantly, these streets were aligned not with wind as might have been expected, but at right angles to it. The only explanation I could come up with for this behavior was the existence of a strong wave pattern above the convective layer. The hunt for wave was on.

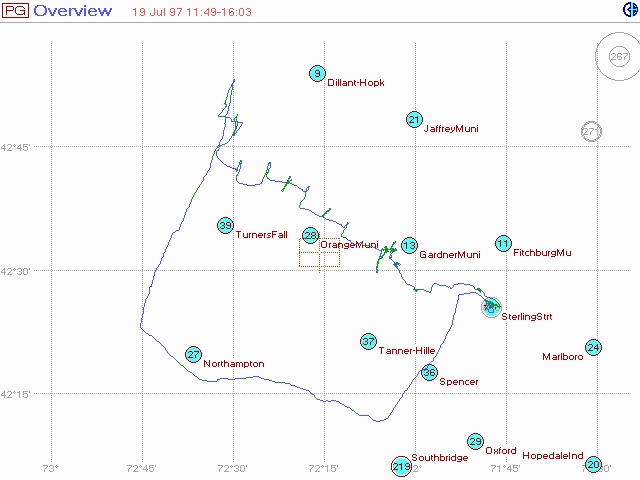

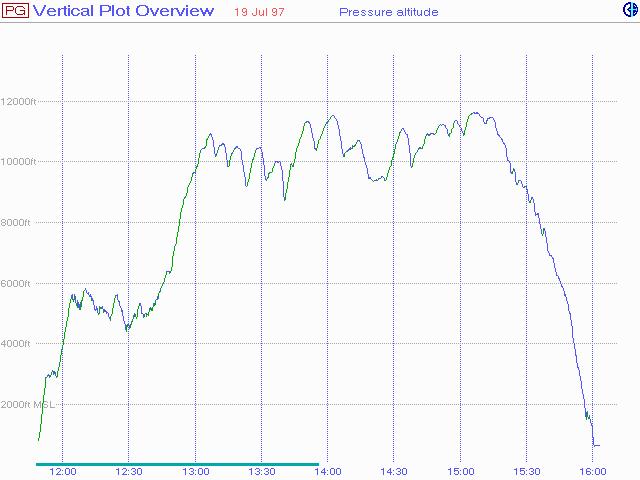

As you can see from the accompanying plots from the flight recorder shown below, contact with the wave was made after a lot of searching to the west and southwest of Gardner airport. Once on top, however, locating the wave was very easy. The location of the waves was evident from the regular pattern they were imposing on the cumulus streets below. All that was necessary was to fly somewhat on the upwind side of the cumulus streets. This also made transitioning to the next wave upwind straightforward.

The plot of the ground track shows a number of excursions at right angles to the general track. These were the result of a beat up and down the wave to regain the height lost in making the upwind jump. I don't recall the outside air temperature, but it was certainly much more comfortable than that on the ground.

Congratulations to all of the MITSA and ex-MITSA participants in the Region One contest the last week of June in Morrisville, Vermont. The weather gods were not with us this year and if you have seen the news you will understand. Parts of Vermont were washed off the map during the week and this was the first contest I have been to where tasks were set up to avoid floods. One contestant had to be assisted by the National Guard to get to the airfield on Saturday. The Sugarbush area received tremendous damage.

Congratulations to Bob Fletcher for coming from behind on the last day to take the Standard Class. He also picked up the Shapiro Trophy for top pilot in the contest. Less than 100 points separated the top five pilots. Phil Gaisford, Mike Newman, and Errol Drew were all in the hunt in Standard Class.

What the official scores do not show are the finals in the Sports class. For the sake of six tenths of a mile, the Sports class did not have a contest. They flew three days, but came up short on day one. So what you do not see in the official scores are the performances of Mark Evans, Bill Brine, Steve Sovis, and Mark Koepper. If it had been a contest I think Mark would have been on top with Bill Brine a close second or third. Steve Sovis also came in second on one day.

One great thing that won't win us any points, but I still feel is worth mentioning, is that MITSA made up over one-third of the registered pilots at this contest. Nine out of twenty-six pilots. No other club even comes close to that number.

One last note. Of course, great weather came the day after the contest. Errol, not wanting to waste a good day, flew home (243K).

Special thanks goes to past member Maria Pirone. Between Maria and Bruce Dyson, they managed to squeeze a contest out of the mess we had that week. On all three contest days the fleet was launched into (in one case) a 90-minute window, meaning that we had rain and/or total cloud cover most of the time, and Maria seem to find a "blue" gap going through each day. Her magic WSI connection also helped.

The FARs and Advisory Circulars (FAA information bulletins called ACs) dealing with airworthiness is not the most glamorous or exciting subject within aviation. In fact, it is about as exciting as watching paint dry. Some areas can even be confusing, vague, or open to interpretation. However, and make no doubt, every pilot has legal responsibilities. The first thing that usually pops into a pilot's mind when you mention "airworthiness" is a preflight inspection or some FAA paperwork that needs to be in an aircraft. There is a bit more to it, including airworthiness directives, repairs, maintenance records, preventive maintenance, annual inspections, and so on. A few glider pilots flying club equipment believe the only thing they need to know about airworthiness or its paperwork is the phone number of the club maintenance officer. If only it were that easy. FAR 91.7(a) and (b) place responsibility for airworthiness directly on every pilot, and we all need to know about the subject.

When I first received my private certificate, about the only time I ever looked at the airworthiness certificate was when I accidentally stumbled across it while searching for something else in the pocket of a 2-33 or 1-26. I knew an annual meant that someone inspected the ship every 12 months and that was good enough for me. I didn't have the time or interest to learn more. After all, I was a young and newly-rated pilot who already knew everything, and besides, I barely had time to rush through a preflight inspection. If I went to a commercial operation or if a buddy let me fly his glider, I just assumed all the paperwork was in order. Again, no need to worry about airworthiness issues, right? Here is where the real world meets the paperwork world. If all the paperwork is not in order, then the aircraft is not legal to fly. The starting point for glider pilots should be a search of the aircraft for its airworthiness certificate, registration, weight and balance, and operating limitations. As we will see, this is only the first step.

An airworthiness certificate is issued when the aircraft conforms to its type design, which means it meets all the specifications and has all the components required as when the manufacturer first obtained certification of the aircraft. FAR 91.203 mandates that each aircraft has an effective U.S. registration certificate, and it is usually kept with the airworthiness certificate. Weight and balance data must be in the glider and may be in the form of placards. If it isn't, the flight manual containing the information must be in the aircraft. The same holds true for operating limitations. How do you know if the glider is rated for spins? What is the never-exceed speed? The information should be on the placards or in the flight manual in the aircraft.

Okay, we have done all this and even preflighted the aircraft. It is now legal to fly, right? Maybe. The FAA Administrator tells us the airworthiness certificate is only valid if the aircraft is in a safe condition for operation. This refers to the condition of the aircraft with respect to wear and deterioration, corrosion, and so on. In other words, we now need to assure ourselves that the aircraft has had an annual inspection. The documentation of the annual is in the maintenance records and these records should not be kept in the aircraft. Only an A&P mechanic holding an inspection authorization can perform an annual inspection. The IA is a person who is authorized to approve return to service for major repairs, alterations, or annual inspections. The ship's annual is a rigorous exam of the aircraft. However, the annual inspection only validates past maintenance and there is no guarantee of future safe operation of the aircraft. Keep in mind it is a bit like an annual physical with your doctor. You might be healthy and fine the day of your exam, but a month later your nose turns blue and falls off. Just because the ship has had an annual doesn't mean the wings are "guaranteed" to stay on for a year. We may need to dig deeper.

Maintenance, preventive maintenance, and repairs are other airworthiness areas where the pilot should have a good knowledge base. FAR 1 defines maintenance as inspection, overhaul, repair, preservation, and the replacement of parts, but excludes preventive maintenance. For our purposes, glider pilots can leave maintenance to the A&P's for performing the work and returning the glider to service. However, FAR 91.405 states there are three areas of responsibility all pilots, operators, or owners need to be aware of. First, we must assure the aircraft has been inspected. Second, we must have any defects repaired between inspections. And, third, we must assure that maintenance personnel make appropriate entries in the maintenance records (we'll list what you need to know later). However, if major repairs or major alterations are performed they are normally entered on FAA form 337.

A surprise to many is that the pilot or owner can perform preventive maintenance. FAR 1 defines preventive maintenance as "simple or minor preservation operations and the replacement of small standard parts not involving complex assembly operations." Examples of preventive maintenance that you can perform is listed in Appendix A of Part 43 of the FARs. Examples of what glider pilots can do would include the following:

One question I had when researching this article dealt with the need to enter a return to service in the maintenance record each time a glider was assembled. I knew that in the mid-80's this matter was a hot topic in the glider community. Indeed, the FAA was well into the process of mandating that the pilot should document "the installation of glider wings and tail surfaces" each time of assembly under a pilot preventive maintenance entry. All of this was to be under FAR 43.9 that would also include a section requiring balloon pilots to do the same for their baskets and burners. The Soaring Society of America along with the Balloon Federation of America mounted a major grass roots lobbying effort that resulted in FAA Amendment 43-27 dated 4/26/87 retracting the assembly entry requirement. The summary of the amendment states the action was taken for "reducing the recording burden on the public." However, Part 61 was modified to require proof of understanding glider assembly as part of the licensing process (FAR 61.107). This was a good idea and the Practical Test Standards added assembly as a task under Ground Operations. One lesson learned was that all of us "odd ball" aviators in gliding, ballooning, and ultra-lights (yes, I know, it hurts me to say "ultra-light" too) could effect change when we combine our numbers.

Speaking of "odd balls," what about the experimental category of gliders. The first time I saw the "EXPERIMENTAL" placard prominently placed in a glider cockpit, I half expected Chuck Yeager to walk up and crawl in for a test flight. Experimental aircraft are usually homebuilt aircraft or imported aircraft that have restrictions. Experimental aircraft are exempt from many of the regulations governing manufactured and standard certificate aircraft. For example, maintenance on homebuilts can be performed by anyone, a pilot or non-pilot. Rather than an annual, a homebuilt glider requires a "condition inspection" to be performed yearly by an A&P or by the original builder who is given a one time "repairman certificate" issued specifically for that individual aircraft. Experimental aircraft usually do not have ADs, but the kit manufacturers do send out bulletins, usually through the Experimental Aircraft Association. Flight instruction can not be given to anyone but the aircraft owner. A homebuilt aircraft requires the builder to have personally done at least 51% of the work for it to be certified experimental amateur built by the FAA. Experimental aircraft cannot be used in commercial operations. Experimental aircraft in general aviation have a similar accident record to standard aircraft when taking into account pilot experience. The liability/insurance issues do not usually vary significantly from standard certificate aircraft. As a glider buyer, I certainly would not exclude a homebuilt experimental aircraft, and in fact, I owned one at one time. You do have to put in some time in research as the designer, builder, and building process are all very important considerations.

Now, let's assume you are vacationing with the family in Aardvark, Arkansas, and you decide to go rent a glider at Jake's Ozark Glider-Rammer where the motto proudly states, "If you fly with us, you'll never forget it." Before entering the airport, you pass under an old bridge with a boy sitting on the rail playing a banjo. You get out of the car and walk towards the office, a beat-up trailer house with flat tires. Jake greets you with a big smile and pulls out a dusty old L-13 that appears to have actually seen combat. You check the cockpit for the required paperwork we have discussed and, being a little concerned, you ask Jake to see the maintenance records. Jake gives you another big smile and leads you to the office. It is your right and your duty, to look at the maintenance records of any aircraft you fly. The ship has a current annual, so it must be in compliance, right? Maybe. If the rental glider is being used for instructional purposes, it also requires a 100-hour inspection, which can be performed by an A&P.

Jake comments, "See, the ol' girl may not be pretty, but she's as solid as a rock." You begin visualizing this glider in the air and thinking "rocks" usually fall better than they fly. Just then a rotund gentleman in the corner belches loudly and you turn to look. Jake introduces you to Big Ed who looks a little glassy-eyed. Jake comments with another smile, "Big Ed is our mechanic." It is time to dig a little deeper into the maintenance records. By the way, you will notice I refer to "maintenance records" versus "maintenance logbooks." FAR 91.417 makes no mention of "logbooks" only records. However, each record must include the description of work performed, date of completion, signature, and certificate number of the person approving the aircraft's return to service for work performed only. Additionally, the records must include a statement on the total time in service (for inspection only) of the glider's airframe, life-limited parts (a part that has a certain number of hours or calendar time after which it must be replaced), the current inspection status, and airworthiness directive (AD) status.

You vaguely remember someone once mentioning that the Blanik L-13 has had a number of ADs over the years, so you sit down and start studying the maintenance records. Each time you look up at Big Ed, you decide it is time well spent. An Airworthiness Directive is the law and complying is not an option. AC 39-7C puts it this way "...the FAA issues ADs when an unsafe condition is found to exist in a product (aircraft, aircraft engine, propeller, or appliance) of a particular type design. ADs are used by the FAA to notify aircraft owners and operators of unsafe conditions and to require their correction. The registered owner or operator of an aircraft (this means you, the glider pilot) is responsible for compliance with ADs. Maintenance personnel are responsible for determining that all applicable airworthiness requirements are met when they accomplish an inspection." There are different types of ADs. In many cases, only a one-time inspection or modification is required to meet the AD compliance. In other cases there may be a recurring AD, an AD requiring periodic inspections, or maybe a part change AD is required. An AD might apply only to specific serial numbers of a certain make or model of a glider or it might apply to all the aircraft of the same make or model. The IA is responsible for assuring an aircraft has complied with all ADs at the time of its annual. Although pilots do not usually check for compliance when renting, we should inquire of the owner, mechanic, or review the maintenance records, as we have a legal responsibility.

What are the practical applications of all the above? Well, there are several, believe it or not.

Bottom line: there are safety, legal, financial, practical, and insurance reasons for becoming familiar with an aircraft's paperwork and plenty of reasons for learning more about the subject of airworthiness. You might want to consider attending one of the FAA's excellent Wings programs dealing with the subject. It may not be as exciting as learning about glider aerobatics, but then again, if you are going to go pull six or seven G's in something unfamiliar, you might want to start with "airworthiness."

The sun is dropping lazily in the west as you put down the maintenance records, but neither Jake nor Big Ed seems particularly troubled by your exhaustive study. In fact, they seem to have enjoyed the whole affair. You can hardly believe it. Everything appears in order with Big Ed's name given as the A&P followed by an appropriate sign off by an IA named Andrew Jackson Willie John Johnson, IV. You chuckle every time you come across the name. You hand the maintenance records back to Jake and comment that the IA has an interesting name. He smiles again and says, "Yep, that's ma given name. Been in the family for mor'en 130 ears. They call me Jake for short." You thank Jake and Big Ed for their time and make a lame excuse about having an emergency dental appointment. On the way to the car you pass by the tired old girl resting peacefully on one wing in the late day sun. She doesn't seem to be in any rush to go anywhere. You note an old dog missing an ear lifting its leg on the rudder while yawning. You decide some soaring adventures are best kept on the ground.

Club email address: mitsa@crl.dec.com

Club web page: http://acro.harvard.edu/MITSA/mitsa_homepg.html

For more information about MITSA, you can contact the club by email, visit our web page, or contact Joe Kwasnik, our director of membership listed above.

The Leading Edge is the newsletter of the MIT Soaring Association, Inc. The newsletter is edited by Mark Tuttle, and published every other month (more frequently during the soaring season). The submission deadline is the first of each month. Please send any inquiries or material for publication to Mark Tuttle, 8 Melanie Lane, Arlington, MA 02174; tuttle@crl.dec.com.