Table of contents:

The original postscript version of the newsletter is available here.New members: We are fortunate to have a number of new members this month.

Joe Kanapka joined the club at the field on Saturday, May 16. Joe writes, "I learned about the club by accident, actually, when I saw a poster near my office at MIT. I've always been interested in flying, and as a child I enjoyed reading books about flying, but I never pursued it any further because of the cost. I was attracted to soaring in particular because of the challenge of it, and finding out about MITSA made me realize it could be affordable, too. I've been out to the field the last few Saturdays, completed eight training flights, and am enjoying it so far. In `real life' I'm a graduate student in computer science at MIT, specializing in numerical methods. I also enjoy music and play clarinet and piano."

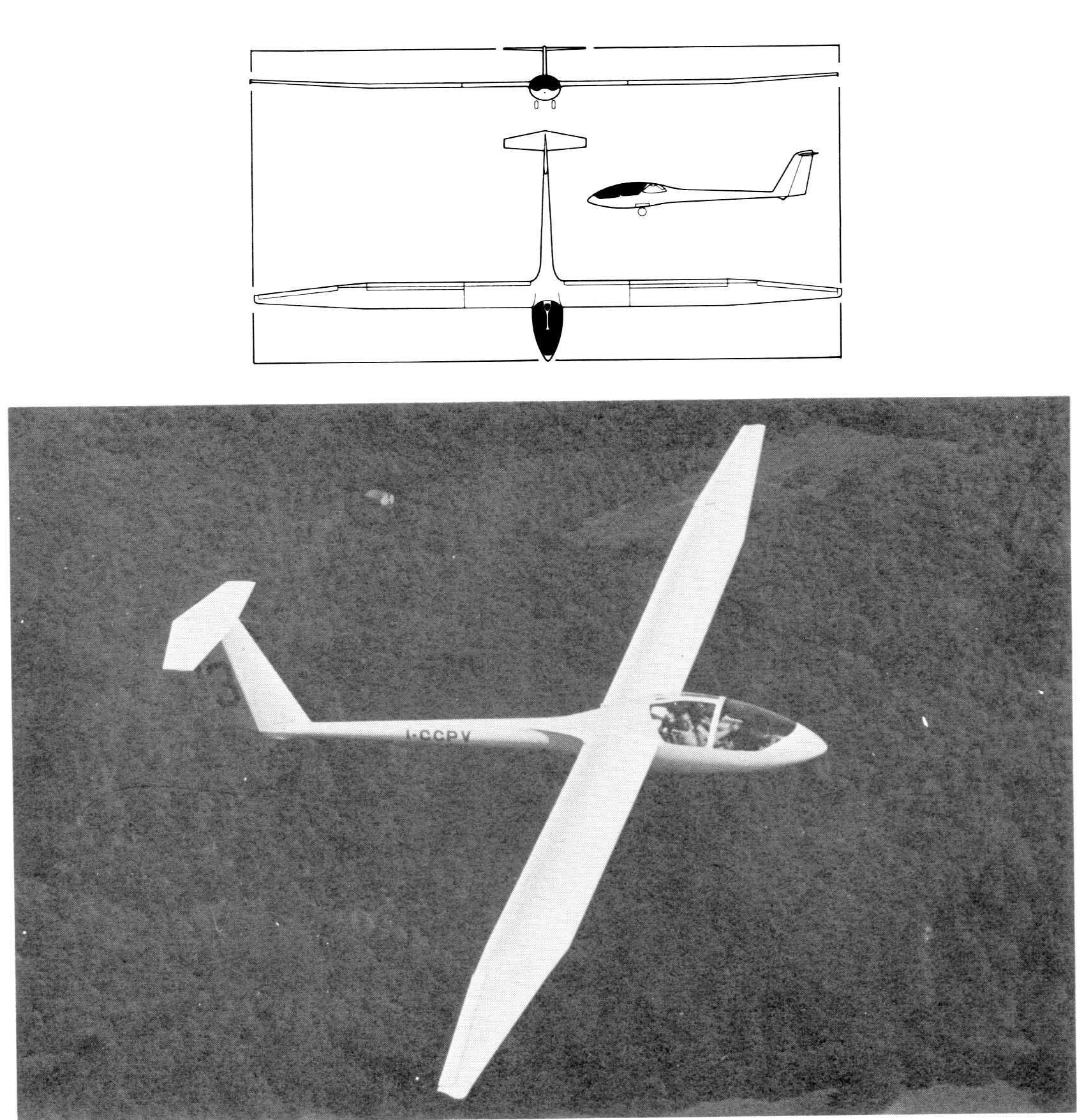

Grant Cary joined the club at the field on Saturday, May 30. Grant says, "I was recently orphaned by the New England Soaring Association when Springfield, Vermont, became their new home. I have known about MITSA, of course, for many years through joint expeditions to Franconia in the mid-seventies, and through friendships with the late Jim Nash-Webber and Roy Bourgeois. My gliding experience was primarily with NESA where I accumulated about 500 hours in both club ships and through private ownership of a Phoebus C and a single-place Lark. I completed my Diamond Badge #US 360 in 1976 and have had extensive experience in thermal, ridge, and wave flying. Other interests include class sail boat racing, wind surfing, and scale model sailplaning. But I must admit that I never fail to be distracted by building cumulus clouds and count gliding as my primary interest. Fortunately, my occupation as an educator has given me sufficient time off to pursue those clouds with vigor. My residence north of Worcester puts me close enough to Sterling to ensure that you will see me at the airport frequently. I hope that I can be a contributing member of MITSA, and I am looking forward to meeting you at the field."

Frederic Bourgault and John Campbell joined on Saturday, June 6. John is getting married during the week of June 15. Mike Newman joined over the winter, but this was never reported in the newsletter.

New certificates: Ken Gassett now holds an ATP certificate with single-engine land and sea ratings. He went down to Florida for training during a winter vacation and picked up the certificate in January.

New pilots: Jakov Kucan wrote on May 29 that, "I have been absent from MITSA activities recently, but I have a good excuse. We just had a daughter last week. Her name is Mia, and both Mia and mother are doing fine. I hope she'll join the club soon, and let me do more flying."

Were you towed by an astronaut? Adam Dershowitz reports, "Some of you might remember that a couple of years ago I brought my friend, Nick Patrick, to MITSA. He joined the club as a tow pilot, and he started flying gliders before he graduated from MIT and moved out of the area. Well, Nick was just accepted by NASA as an astronaut, so he will get a chance to go from flying '094 to flying in the biggest glider...the space shuttle."

Good soaring: The Memorial Day weekend had some good soaring. Phil Gaisford reports that on Saturday there was wave to 8,000 feet over the airport with wave to 15,000 feet near North Adams. Bob Fletcher (90) flew to North Adams and back, Phil Gaisford (PG) flew to North Adams then Keene and back, and Doug Jacobs (DJ) flew to Sugarbush. Phil says that Sunday was poor thermals under a relatively low inversion, no cumulus, and quite windy, like so many days this year.

The weekend of May 30-31 was not a very good soaring weekend. Saturday, May 30, was reported to be a scratchy day. Since Steve Sovis has the Grob on Saturdays, I didn't go out myself, but I did fly a Piper Cherokee on a joy-ride down to New Haven, and since the ride was the most glassy-smooth ride I've had in months, I conclude that there was little convection in the atmosphere that afternoon.

Sunday, May 31, was the big day of convective sigmets. My early morning briefing mentioned thunderstorms late in the day, but I went out anyway for at least some pattern tows in the morning. What I found at the airport was wave after wave of heavy showers being pushed over Sterling by a warm front coming up from the south. Between two of the showers, we looked at the sky, someone said, "Hey, it's clearing," and immediately after that we heard the thunder from the next shower rumbling in the distance. I gave up and drove home, and on the way I looked west from a high point on I-190 and saw cell of heavy rain west of Wachusett so dark and perfectly cylindrical that it looked like a finger extending down from the sky and pressing into the ground. A few minutes later the radio reported dime-sized hail at Gardner. The sky cleared a bit for a few hours. I hear that GBSC members took two or three sleigh rides in one of their 2-33's, and Al Gold, Joe Kwasnik, and Bernie Loraditch polished the Gold-Kwasnik 1-26. Then that evening, New England was treated to the heavy thunderstorms ahead of the fast-moving cold front that flattened Spencer, South Dakota. A torrential band of rain swept across the state at a speed of 50 miles per hour, Worcester airport reported wind at 94 miles per hour, there were two tornadoes in Worcester county, and some kind of microburst in Winchendon, New Hampshire, a half hour north of Sterling split a tree a foot-and-a-half thick and dropped the top of the tree onto a car. That evening the recorded briefing summary for a five-zero nautical mile radius of Boston, Massachusetts, said, "VFR flight not recommended." All flight not recommended, in my opinion.

Sunday, June 7, I gave up and drove home in heavy rain, and Al Gold reported that there were interesting funnel clouds visible northeast of Fitchburg and about 10 miles south of Sterling.

Wave camp: Mike Baxa is trying to organize a wave camp for private owners at the Gorham Airport in Gorham, New Hampshire, at the base of Mount Washington. Mike says, "Mount Washington is the place for those who would like to try high-altitude flight or experience mountain soaring (thermal, ridge, and wave). Gorham has a wave window, so flights well over 20,000 feet are routine when the winds blow at 40 knots or more over the peak. The flying and scenery are simply spectacular." If you are interested, contact Mike at (860) 870-0018 or michael_baxa@ipmscorp.com.

Record flights: The magazine Flying reports that the National Aeronautic Association (http://naa.ycg.org) has named the top ten record flights of 1997. One of the flights mentioned is by "Karl Striedieck, who flew a Schleicher sailplane nonstop from Mill Hall, Pennsylvania, to Selma, Alabama, a distance of 800 miles."

Sterling safety seminar: Mike Baxa reports that the FAA is holding a Safety Program seminar in Sterling on Thursday, July 23, at 7:30 pm at the First Church and Meeting House. The title is "Operations at nontowered airports." The seminar description says, "Most general aviation flying starts or ends at nontowered airports. Far too often it seems that when more than one aircraft is in the pattern, there is a breakdown in effectiveness. This session will review `proper' standardized procedures for operating at nontowered airports and discuss some of the pitfalls involved. Share your experiences and insights with fellow aviators at this important session." The seminar is sponsored by MITSA, Sterling Air, GBSC, and Liebfried Aviation. To get to the seminar, take exit 6 off I-190, take Route 12 South into the center of Sterling, and the church is on the common in the center.

Since Homo sapiens first scratched themselves while staring into the sky, man has complained about the weather. We have all heard the saying, "Everyone complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it." Well, for the first time in human existence, man has finally done something about it and what does everyone do? We complain about it. Sure, El Nino and global warning is not everyone's cup of tea, but at least let's give credit when credit is due. Yes, I know homes are sliding into the pacific given El Nino rains, but, hey, I was just out there last summer and they were complaining about the low water tables. True, if the polar caps melt we have big problems, but I saw the movie Waterworld and there is a lot to be said about the freedom of roaming the earth on your own armed trimaran. You've got to look on the bright side of things.

The weather is what challenges each of us and provides unending variables making each flight unique. Although you can read weather books until you go blind, you will not gain the necessary skills, knowledge, or full understanding of weather without experiencing its characteristics in flight. However, a starting point is understanding the dynamics involved in what is a good soaring condition and what is potentially dangerous. Despite today's high tech equipment and sophistication, weather forecasting for a specific locale at a specific time remains only fair to poor. Local weather variables are too many, too complex, and in constant change. The most reliable forecasting team for a given locale and time is composed of the FAA briefer and the guy you see in the mirror. I do believe that we as pilots need to adopt the attitude of our salt water sailing friends. A good sailor has a love for the sea balanced by a healthy dose of respect and fear. Just like the sea, our ocean of air can turn from being a tranquil sleeping beauty into a wretched and vengeful monster. We'll focus on a few characteristics of this monster when it is not in a good mood, or at least feeling a little feisty.

An inversion is where you have an increase in temperature with altitude. Ground inversions usually begin on clear and cool still nights when the earth begins cooling the surface air. You then have a warmer air mass on top of a cooler air mass. The upper air mass is moving in a different direction and speed than the lower air mass. If you watch enough launches over a few seasons, you will eventually witness the tow plane doing a normal climb only to begin erratic pitching and wing rocking at a few hundred feet above the ground, followed by the glider doing the same. They are passing through the boundary layer of an inversion. The layer can be turbulent with whirlpools of air circulating in different directions. It is often much like passing through the down wash of the tow plane going from high tow to low tow. However, it can be much stronger. A ground inversion is a source of wind shear, and wind shear is something every pilot should fear.

Inversions can be found at any altitude in the troposphere (from the surface to an average altitude of 37,000 feet, depending on location and season). They pose the greatest threat to safety on take off and landing, when you are closest to the ground. The abrupt change in wind direction and wind speed may bring your aircraft to stalling speed. If you suspect an inversion, carry added speed. Ground inversions usually disappear as the day wears on with the upper air mass overcoming (blowing away) the lower air mass. However, this is not always the case. An inversion may settle in over a region, trapping fog and smoke. We then have those hazy days with little to no convection. Besides the reduced visibility of haze, we have to contend with the optical illusion of objects appearing further away than they really are. Thus, aircraft may be much closer than our brains are telling us.

Several years back I owned a HP-14 for a couple of years (all metal V-tail with no air brakes but full flaps). A front was passing through and in the late afternoon it became very gusty. It was turbulent and the thermals were being blown apart so I headed for the deck. I knew the HP could be a little slippery in crosswind landings so I was carrying a good ten knots of extra speed. I was on downwind just ready to turn onto base leg, when the ship stalled in mid-air. The controls went mushy and my ground speed, which had been very fast, slowed to very little. I pushed the stick forward, and it seemed like an eternity before I had regained sufficient speed for control effectiveness. Given my very low altitude, I abandoned the pattern and did a diagonal landing on the field. I had encountered wind shear created by a frontal passage. If I had been slower and in the middle of my base leg turn, the ship could have easily stalled and/or entered a spin. Wind shear has been a factor in many airline disasters and should not be underestimated. Since that day, right or wrong, I became an advocate of high-energy landings, always fearful of wind shear.

Fronts, as discussed, are sources of wind shear, but why or how? It begins with an understanding of air masses. An air mass takes on the properties of its earth source: for example, the cold arctic air was originally cooled by the polar cap terrain. This colder air tends to be a high-pressure area (cold air is more dense, thus more weight or higher pressure exerted). This air retains its original properties of temperature, humidity, and pressure. High-pressure areas migrate to low-pressure areas trying to equalize the pressure differences, earth's endless cycle. The earth's rotation and centrifugal force deflect these moving high-pressure areas. Rather than the high-pressure air rushing into the low, the high-pressure air begins a circular flow. This is the Coriolis effect. In the Northern Hemisphere, winds in a low blow counter-clockwise and highs blow clockwise. If you stand with your back to the wind, the low will be to your left and the high will be to your right. We know there are three types of fronts (warm, cold, and stationary). A cold front moves almost as fast as the speed of the wind, while a warm front moves about one-half its wind speed. The zone between adjacent air masses is called a front or frontal zone. The wind always changes across a front. In this zone of no-man's land the temperature, humidity, and wind changes rapidly in an almost confused state of turmoil. This zone is often an area of turbulent air including wind shear.

Scientists are just beginning to unravel some of the complexities of weather fronts and questioning long standing weather models. For example, power pilots have long been aware that squall lines can develop hundreds of miles ahead of a passing cold front. Behind this squall line, the air can be very turbulent. It appears a moving cold front often disconnects into a surface cold front and an upper air cold front. The upper air cold front moves much faster than its low-level sister thus triggering an advance squall line over the warmer air. Although a passing high-pressure cold front holds great promise to the soaring pilot, we do need to respect a passing front, as wind shear may be present. The best way to determine a front's arrival is with a good weather briefing.

Wind shear can also be generated via mechanical turbulence when the wind encounters obstacles such as mountains or even buildings. The wind hits a large object and diverts in various directions setting up eddies and whirlpools. In mountain soaring and even ridge soaring, you need to be continually vigilant. You often have to fly a hundred feet or much less from the sloping terrain to stay in the strongest lift. Doing so means you need to be continually on guard for shifting winds, down drafts, and wind shear. Your salvation is carrying sufficient speed to overcome the variable conditions and make a quick escape into the valley. Again, you just need to keep anticipating and be prepared for prompt action when flying in windy conditions. We can gauge surface winds with the wind sock. If the wind sock is hanging straight down, surface winds are light and under five knots. If the sock is pushing out at a 45-degree angle, the wind speed is five to ten knots. If the sock is blowing straight out, the surface winds are 15 knots or greater. Again, a wind sock can only give indications of surface winds, which is only helpful when landing or taking off.

Recently, I was chatting with our chief instructor, John Wren. We agree that there appears to be a growing gap between the moderately-experienced cross-country pilots (I barely fall into this category), and those that are able to fly 300 miles on a day where I get nervous at 3,000 feet and only 10 miles out. There is also a growing number of private rated pilots that would consider a 10 mile trip from home a new personal record. We thought it might be a good time to reacquaint membership with the SSA Badge Program. I enjoy an afternoon of aimlessly punching holes in the sky as much as the next guy. However, it is not very challenging. Becoming a better and safer pilot also means setting realistic and attainable goals that moves a pilot to a higher experience level. The ABC Bronze Badge Program does exactly that.

The requirements for any of these badges can be obtained from a MITSA/SSA instructor or by contacting the Soaring Society of America. For each badge, the applicant demonstrates progressive knowledge and skill. For example, the B Badge requirement is a solo flight of at least 30 minutes in duration from a 2,000 foot agl tow (if you go higher, add 1.5 minutes per 100 feet above 2,000 feet). Hey guys, except for non-solo students, you all have this one nailed. To give you that well-deserved recognition, an SSA instructor can write up your badge completion certificate on the field and award you a badge pin on site. Your name will also be submitted to the SSA and appear in Soaring magazine. The C Badge is designed for cross-country preparation. Cross-country knowledge needs to be demonstrated, a solo flight of 60 minutes, and an accuracy landing touching down and stopping within 500 feet. Additionally while with an instructor, you need to complete a simulated off-field landing approach without reference to an altimeter.

Completion of the Bronze Badge reflects your cross-country readiness. The flight skills and knowledge criteria is a little tougher now and includes a closed-book written examination covering cross-country techniques and knowledge with a passing score of 80%. An SSA instructor can help you prepare for this exam and administer the test.

You are now ready to move from the minor leagues to the majors. Your silver, gold, and diamond badges are waiting. Your height, distance, and duration badge leg flights are administered by the SSA for the Federation Aeronautic Internationale (FAI). An instructor, the SSA, or a fellow club member holding one of these badges can be of help in introducing the requirements. The procedures and required documentation needs to be closely studied. Formal application, initialed barograph traces, and a qualified observer are a few of the requirements. If you do not think pursuing your silver, gold, or diamond badge is worth the effort, look in the back of the next issue of Soaring and call anyone of those folks listed under "Badge and Records." Each would have exciting adventures to share. You would also quickly sense the pride of accomplishment with each story. Yes, pursuing badges is worth it. You will be challenged to improve your skills, rewarded with recognition, and you will become a better and safer pilot.

Wind shear is not uncommon with inversions, fronts, and mechanical obstructions. Another source is with the "mother of mothers" for weather phenomena, the thunderstorm. Twenty years ago, I watched the strangest weather phenomena I believe I have ever seen and that includes Northwest Pacific gales to several tropical cyclones. At the time I was living in western Nebraska and it was Sunday afternoon. Tornado warnings were being broadcast on the radio when I went outside to the darkening sky. All the neighbors were out on their front yards staring at the sky. The air was perfectly still without even a bird chirping. At about 300 feet agl there was a layer of Cumulonimbus Mamma clouds churning like hell's furry. It is hard to describe, but imagine the entire sky with these rounded grayish brown masses hanging from the sky like giant pillows. The sky had the appearance it was boiling. It was a sight to see. Occasionally a funnel cloud tip would start to dip down only to be sucked up again. Suddenly the hot air chilled 20 degrees in seconds and everyone ran for their house. Hail came down the size of baseballs. Windows began shattering and the wind began toppling trees. After the storm, people began emerging. On close inspection of my neighbor's home across the street, there were holes punched all the way through the exposed north side of his house. You could literally look into his living room. He had gone on a delayed vacation the week before waiting for the workmen to finish the new siding on his house. Don't fly close to a building cu-nim, no matter how tempting those dark flat bottoms look. FAA Advisory Circular #00-24B recommends a lateral distance of 20 miles from a severe storm. There are downdrafts, updrafts, and even microbursts. An intense microburst can produce small radius downdrafts as high as 150 knots. Besides all this, you risk hail, lighting, and/or a rain downpour, which not only eliminates visibility, but also makes your L/D on your fiberglass bird slightly better than a primary glider.

I never really appreciated what the big deal was over "density altitude" until one hot and somewhat humid summer afternoon soon after I had gotten my Nimbus. I was going to practice my flying techniques with full water ballast. You're right, it wasn't the brightest thing I have ever done. I should have instead stayed on the ground learning about the effect of density altitude. If my tug hadn't been a high-powered L-19 with a gutsy tow pilot at the controls, I would probably still be picking fiberglass splinters out of my gluteus maximus. We almost ran out of runway. Density altitude is succinctly defined as "the altitude in the standard atmosphere at which the air has the same density as the air at the point in question." Say again. I have read less confusing statements in my VCR programming manual.

Let's try the backdoor approach to this density altitude thing. Air can vary in its density or "thickness." The more molecules of air in a given space, the more thick or dense the air is. The more dense the air, the better the performance of our airfoils or wings because we have more air molecules passing under and over in a given period of time, thus generating more lift. Anything that decreases the density of the air or makes it "thinner" negatively impacts on the performance of our wings. The three things that determine air density are pressure (weight of the atmosphere), temperature, and humidity. The higher you fly, the less the atmospheric pressure as the air becomes thinner. The air molecules are not being compacted as much as they are at lower altitudes, due to gravity. Increasing temperature results in something similar. The air molecules become excited, bump into each other and spread out, thus resulting in the air becoming thinner. Again, not a good thing for airfoil performance. High humidity translates to additional water molecules in the air, which displace some of the air molecules, and thus, the air becomes thinner. In high humidity the air may feel thick, but remember the air molecules are more spread out or thinner, and this also is not good for airfoils. Density altitude is really not a reference to height. It is an indicator or index to aircraft performance.

High density altitude (thin air) reduces the performance of aircraft. (If nothing else, commit this statement to memory.) The worst-case example would be taking off with a heavily-weighted trainer at the Denver airport (higher altitude, thinner air) on a hot (higher temperature, thinner air) and humid day (higher humidity, thinner air). In such an example, you may not even be able to get the wings off the ground. High density altitude lengthens your take off and landing roll, and reduces your rate of climb. These same factors affect the tow plane. Plus, because the tow plane uses a propeller, which is also an airfoil, the propeller is not as efficient. Finally, the thin air reduces the engine performance because the engine is sucking less air. My point is high density altitude is a weather factor every pilot needs to understand and respect. The sneaky thing about high density altitude is that your airspeed indicator works the same with one big difference. Your actual ground speed or true airspeed is proportionately higher (the higher the density altitude, the higher your ground speed and true airspeed). Relax, I am not going to explain why. Whew... If any of you figure out what I said in the above paragraphs, please call and explain it to me.

We discussed earlier the value of getting a weather briefing. Yes, I know you can turn on the Weather Channel or pull down numerous weather sites on the web. However, nothing replaces talking with a trained professional for the current data and/or projections for a given time and locale. The National Weather Service (NWS) works closely with the FAA in providing weather service to the aviation community. FAA personnel at Flight Service Stations primarily give pilot weather briefings. These folks are certified by the NWS as Pilot Weather Briefers. Although they are not authorized to make original forecasts, they are authorized to translate or interpret forecasts as they relate to your flight. Pilot Briefers are available around the clock and can be accessed by phone (1-800-WX-BRIEF). This same number works for obtaining a continuous recording of meteorological conditions via TIBS (Telephone Information Briefing Service). TIBS should be used as a preliminary source in making those "go to the field or don't go" decisions. The three basic types of briefings include the Standard Briefing, the Abbreviated Briefing, and the Outlook Briefing. Generally, the Standard Briefing will serve the glider pilot's needs. If you are planning a flight more than six hours in advance, you should then request an Outlook Briefing.

The Standard Briefing will include the following information: adverse conditions, whether VFR flight is or is not recommended, synopsis of weather system or air mass movement, current conditions, an en-route forecast if going cross-country and a destination forecast, winds aloft, and any Notices to Airmen (NOTAMS). Do not ask for a thermal index, as this information is not available to the briefer. You will need to give the briefer the N number of your aircraft or club ship and advise the briefer you are a glider pilot. Tell him the "when and where" you intend to fly and request a Standard Briefing. Given we are located adjacent to Worcester, Massachusetts, I usually request a Terminal Forecast for Worcester. Have a pen and notepad close by. Ask for clarification or to repeat information when you are unsure. These folks are very busy and tend to talk rather quickly.

Until the polar caps melt, we should all fear life as we know it if climatic changes begin affecting our soaring season. I believe it is time for soaring pilots to get organized and start lobbying Congress. There are special interest and victims groups for everything else, why not government subsidized field and forest burning for soaring enthusiasts "traumatized" by adverse weather? Each SSA Region would control the weekend thermal schedule for having grain crops and timberlands burned. It would be a financial shot in the arm for farmers. It would take the political heat off the peasants in South America burning the rain forests. And, it would give those volunteer firemen with the funny blue lights something to do on weekends. So much for the pragmatic political commentary, I just hope the meteor being hyped by the news media hits earth soon. It will set off volcanoes everywhere. The rate of climb under one of those suckers has got to be impressive and it would add a whole new dimension to cross-country badge work. Keep thinking those positive thoughts!

These minutes have been edited for publication in the newsletter. --Editor

June 4, 1998

All members of the board plus John Wren were present, except for Steve Glow and Carl Johnson.

Sterling operations: Several comments indicated that ground communications using the walkie-talkies was not working. It was concluded that henceforth ground communications should be by VHF radio on 123.5 MHz using handheld and ship radio sets. John Wren indicated that he may have a VHF rig that could be used as a base radio, given some volunteer technical assistance to set it up. The Airport Manager at Sterling, has requested that private cars not be driven on the taxiways. Several members have argued that it is difficult to run a glider operation without using private cars, particularly with the current status of the golf carts. It was agreed that we must honor the manager's request while at the same time seeking a more liberal policy from him on the limited use of cars under special circumstances. If this is to be accomplished, it is imperative that car and golf cart drivers exercise safe and cautious driving habits everywhere around the field. A single unsafe incident associated with the glider ground operation will work against a more liberal policy on the use of private cars.

New tow plane: Bruce Easom reported for the tow plane committee that a two seat, tail dragger such as a Scout in the $40,000-$60,000 range was considered the best choice for our operation. The president is drafting a letter to the membership giving the rational for the new tow plane, a report on progress, and a request for comments. The committee is searching for an available Scout.

Relations with GBSC: Carl Johnson had reported that talks with GBSC are going well. The operational issues are mostly smoothed out, and the relationship at the field has been very cordial. The President outlined a plan to discount our annual dues to full members of GBSC so that they could join MITSA for one year for something around $100. This plan has the advantages of providing incremental dues income, additional tow income, and a very friendly gesture towards GBSC members that would be reciprocated. It was moved, seconded, and passed that the president should proceed with the offer.

Membership: Joe Kwasnik introduced a plan to revamp the MITSA brochure and make new advertising posters. It was suggested that T-shirts and SOAR MITSA bumper stickers be added to the plan. Joe will get an estimate of the costs and then proceed. John Wren said we should take advantage of MITSA's strength and reputation in the area of cross-country soaring to attract members. He offered to update the MITSA web-site to play up cross-country soaring and consider offering another cross-country course.

Maintenance: Jim Emken described a plan for a 150-foot anchored cable as a tie-down for trailers to protect them against damage in high winds. Bruce Easom is to check with Simpson Construction about some of the details of anchoring the cable. There were some instrument repairs to the 1-34 completed and there is an AD for wing repair on the L-33 to be completed before 1,200 hours total time. Our L-33 currently has about 300 hours.

Next meeting: The next meeting is Thursday, July 9.

A message in rec.aviation.soaring described a USAF C5 flying at 600 feet through the downwind leg of the approach to a glider port in New Castle, Great Britain, on May 15. Since this was shortly after the Italian ski lift disaster, this message generated a long string of stories about near misses with low-flying military aircraft. John Wren posted the following story about his own close encounter in Great Britain in the mid-1970's. --Editor

Many years ago, while serving in the USAF in the UK, I learned to fly gliders at Ink Pen Ridge. During that period, RAF Upper Heyford shut down to repave its runway and moved a lot of its planes to RAF Greenham Common. In preparation for the move, the USAF had a media blitz to all of the local flying clubs. The main point was they were concerned that we would get in their way. During their briefing to our club, they passed out maps pointing out the area we had to stay out of. They went on to say how great their pilots were, and if they strayed just 200 yards off the center line of their approach, the crew would be grounded and sent back to the states for further training.

A few days before the start of the Nationals (at Lasham), I was at FL45 above Ink Pen (now Shalborne GC) and about six miles south of their "red" area (I had their map strapped to my leg). There were a lot of gliders in the area practicing from Lasham. I flew an ASW-15 at the time and had just leveled out for a second to center in the thermal. In that split second, the first thing I remember was the stick vibrating at a very high frequency. There was also a faint dull, droning sound. Then BANG BANG, two F-111's passed 20 to 30 feet above and either side of me. In the next second I waited for the third bang which was the turbulence behind them ripping my glider apart. But that must be what movies are made of, because in reality I felt nothing and was still going up at four knots.

Shaken, I made a call on the glider frequency, pulled my air brakes, and landed back at Ink Pen. The CFI at the club suggested I file a near miss with the CAA, and I did so. A few days later we were all at Lasham for the Nationals, and by a twist of fate the USAF were the guests of the opening day of the contest. Later in the day I was strapped into Mike Carlton's Calif for a demo ride. Two F-111 jocks (in flight suits) walked up and I was bumped. While one was being strapped in, we (the Ink Pen CFI and I) asked if they had received a "near miss" report. The answer was, "Is that the one with the two F-111's and the glider?" "Yes," I said. "No, we haven't heard a thing about it," they said. Now I was really upset, not only had I been nearly taken out of the sky by these nuts, who were quite arrogant, but now I had missed out on a ride in a Caproni.

Six months later, the report came back and no fault was found. The F-111's had "declared an in flight emergency...smoke in the cockpit..." Funny, I didn't see any smoke.

Let's start with Jennifer, now three years ... oops, three and a half years old. Jennifer's nanny, a French girl of Algerian origin, left us for greener pastures (Paris) at the end of June and was replaced by an au-pair from Liverpool. Since Laura arrived with little or no knowledge of French, this resulted in a dramatic improvement of Jennifer's English. Very positive and all, but it also means that her parents cannot discuss anything in English that Jennifer should not hear. Moreover, she has a particular good ear for those things she should not hear. This then results in questions like: "Mamma, pourquoi `Oh shit?"' Another aspect of, we believe, her going to school is that she has developed very strong ideas as to what is acceptable clothing and what is not. We have tried to cope with this by letting Jennifer pick out her clothes at the store so that we do not get into the situation where a brand-new pair of pants or sweater is rejected. Sounds good, but when the only acceptable shoes in the store are of the bright red, fake lizard leather variety, us conservative parents sometimes despair. (These shoes are for some reason very popular in France. Ariane was about to tell a colleague of the horrible shoes Jennifer had wanted to buy when she noticed that the colleague had the same shoes ... Ariane quickly switched to the weather.)

Enno? Well, Enno finally came to the conclusion that R&D was not only a lot of fun but also a bit of a dead end. Especially the aspect of having others (Marketing) tell you want to develop. So Enno has been driving through Bavaria for the second half of 97, visiting customers as sales representative/coagulation expert. [Enno works for a company that sells equipment and supplies to medical laboratories, including tests for assessing the blood coagulation status of a patient.] Since coagulation sales in his region have been going up, he is happily claiming to be the father. How things will develop next year is still a bit uncertain since the company that Enno works for (Boehringer Mannheim) has been bought by Roche and at the moment everything is in the twilight zone between the announcement and approval by the various government bodies that supposedly safeguard competition. Only when the merger has been formally approved will it be possible to reassign people and start new projects. Nevertheless, it is not likely that Enno will be doing R&D for another seven years. As for other fun things, for a variety of reasons Enno was not able to do as much soaring as he would have liked to, but with some fifty hours of flying time, the year was at least not a complete wash-out... but he made one goof-up. Last August, as he prepared for a landing he must have failed to lock the landing gear so that when he touched down (and it was a perfect touch down, he says... the other club members have their own thoughts), the landing gear promptly disappeared. Afterwards there was a long white stripe on the runway and the chief instructor of the club was not pleased at all. Oh, well...

Last but not least, Ariane, who this year spent much less time than she would have liked in a glider. Still she managed her first flight in a single-seater, a nervous little machine which made her even more nervous when she realized how fast it responded to the controls and how difficult it was consequently to land and keep in the middle of the runway... but over all she had fun. To compensate for the little time spent soaring, Ariane collected well over 100,000 miles in the Air France frequent flyer program and so probably flew more than Father Christmas. Jennifer now has sweat shirts from Miami, Chicago, sweaters from Bolivia, and so on. [...]

We had quite a few visitors in Lyon this year who were surprised to discover how nice the city was. We remind everybody that Lyon has quite good connections to the rest of Europe, is close to the ski slopes, to Provence, and only two hours from Paris by train. There is really no excuse not to stop by and discover the former capital of Gaul, to explore the real estate, from Roman theaters to 19th century English parks, not to mention the Renaissance old town.

Chris was an active member of the club and of the board for years. He graduated from MIT around 1994 and left to become a professor of physics at the University of California at San Diego where he reported that he was trying to figure out how to "cool and trap positrons so that we can make anti-hydrogen" and studying aerobatics in a Decathlon. He stunned us all in 1997 by taking a management position in a power company back home in Austria. Now you can contact Chris yourself at ckurz@bnet.at. --Editor

The small individual European electricity markets will join early next year to form one big European market, which is the big event everyone is preparing for in the business. I am supposed to help make this transition at my company. So that's what I do right now from eight to five. Besides that, I am about to get back into flying again. The weather has been great, sunny, and soarable lately.

I live about 20 minutes from Wiener Neustadt, the place where the 1991 (I think) soaring world championship was held. It's a place with six nice, long grass runways, practically no power traffic, and within easy gliding range to ridges, wave areas, and thermal lift soaring. On a good day there can be easily up to 100 gliders in the air. The field is host to about ten soaring clubs of varying size. Let me give you some details on the one I am about to join.

It has about 150 members (many own their own planes) and an impressive club fleet: three LS-4s, four Blanik trainers, a Janus, six or seven Ka-6s and Ka-8s, a Libelle, an ASW-25, a couple of Grobs, and maybe a few more glass ships that I have forgotten. Launching is either by aero-tow (with a Husky) or winch. Their winch is new (they built it in the club) and will get gliders up to anywhere between 1,000 to 3,000 feet depending on wind and length of rope.

The club prices (in US dollars) are as follows. The initiation fee is $400, the annual dues is $400 for adults and $275 for students, and a one-time membership is $40. An 1,000-foot aero-tow is $10 or $12 in a single- or double-seater, respectively, with each additional 300 feet costing $3, and a winch launch is $6.

Each member is expected to put in 40 hours of time per year. If someone is unable or unwilling to contribute that much, there are three options: pay an additional $310 on annual dues with no obligation to work; pay $12 for each hour short of the 40 hours per annum; or pay $23 on hourly rental fee per plane with no obligation to work (this is for infrequently flying members or one-time members). There are plenty of jobs available in which members may contribute their time (time keeper, shop work, electronics technician, building work, DO, tow pilot, winch operator).

There is no fee for instruction and no rental fee for gliders. What I found interesting is the way they allot gliders to their members. All cross-country pilots in the club are ranked according to their flights in the previous year. All gliders are on a list with the best planes on top. Each cross-country glider (that is, the glass ships) then gets assigned a pilot (maximum three pilots) starting from the top of the pilot list. In this way, good cross-country pilots get assigned to the best planes. This assignment is for the duration of one year, which means that effectively you own the plane for a year, shared with at most two other people. The club policy encourages cross-country flying, and its infrastructure supports it effectively. There is a barograph for each cross-country glider, and a roomy club workshop which lets owners do their own maintenance without having to buy all the tools. It's comforting to know that their is enough know-how in the club to assist in difficult situations, should one arise.

The area is prefect for all kinds of soaring. Most long distance flights go off toward the west and into the Alps for ridge, wave, and thermal soaring. 300K flights are nothing to write home about, I have been told. Fields for landing out in this area, as you can imagine, are scarce. Pilots know all the important opportunities by heart and are very careful about venturing into areas where there are none. Altitudes is, of course, your friend, and there is plenty to be had around here. I have it from good authority that people go up to 10,000 feet and above regularly. You launch around mid-morning and will find yourself soaring until sunset, around 8 or 9 pm in the evening. I can't wait to be circling the moon!

As good as the situation is for gliders, as bad is it for flying power planes. Prices are high (a Cessna 172 or equivalent rents for $110 per hour), landing fees are common, and airspace is crammed (albeit not crowded).

That's the news (not from Lake Wobegone) from Austria.

We, the private owners, need to be more disciplined in our griding arrangements. We have had a few days when the private owners have herded to the 34 launch point and parked leaving insufficient space for GBSC aircraft. This is contrary to courteous behavior and procedures agreed between the two clubs. Here's the procedure:

A note to grid officers: these arrangements will be impossible to implement without the cooperation of many individuals. If a pilot appears to be having difficulty following these guidelines, feel free to refer him to a Board member.

I am aware that this is not as convenient an arrangement as when we had Sterling to ourselves, but be assured that the Board is actively working on ways of improving the launch operation. As always, let us know if you would like to help. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the input of Doug Jacobs, many of whose ideas are incorporated in the above.

Club email address: mitsa@crl.dec.com

Club web page: http://acro.harvard.edu/MITSA/mitsa_homepg.html

For more information about MITSA, you can contact the club by email, visit our web page, or contact Joe Kwasnik, our director of membership listed above.

The Leading Edge is the newsletter of the MIT Soaring Association, Inc. The newsletter is edited by Mark Tuttle, and published every other month (more frequently during the soaring season). The submission deadline is the first of each month. Please send any inquiries or material for publication to Mark Tuttle, 8 Melanie Lane, Arlington, MA 02174; tuttle@crl.dec.com.